At the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914, Britain has a small highly skilled professional army consisting of some 247,432 officers and men. The British Expeditionary Force took 100,000 men to France and it very quickly became clear that the regular army was incapable of waging war alone.

Lord Kitchener, a national hero of the Sudan and South African campaigns, was appointed Secretary of State for War on 5 August 1914. Even at that time, he was one of the few leading soldiers who foresaw a long and costly war and that the professional army would be far too small to play an influential part in what was clearly going to be a major European war.

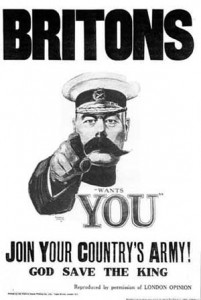

Kitchener announced to a stunned cabinet that at least one million additional men would be needed in the armed forces. On 7 August 1914, Kitchener appealed for the first 100,000 volunteers to form his ‘New Armies’. He also permitted the part-time Territorial Force – originally intended primarily for home defence – to expand and to volunteer for active service overseas. There was no conscription of population before 1916, and so recruitment of volunteers in large numbers became a huge challenge.

Peter Simkins writes on the British Library website:

“After a relatively slow start, there was a sudden surge in recruiting in late August and early September 1914. In all, 478,893 men joined the army between 4 August and 12 September, including 33,204 on 3 September alone – the highest daily total of the war and more than the average annual intake in the years immediately before 1914. Apart from a bedrock of patriotism and a widespread collective sense of duty to King and Empire, two factors, in particular, helped to generate this boom in enlistment. One was the formation on 31 August of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee (PRC), which placed at the disposal of the War Office the entire network of local party political organisations. The assistance which the PRC provided included the issue of a series of memorable recruiting posters designed by leading graphic artists of the day. Another key factor in stimulating enlistment was the granting of permission to committees of municipal officials, industrialists and other dignitaries, especially in northern England, to organise locally-raised ‘Pals’ battalions, which men from the same community or workplace were encouraged to join on the understanding that they would train and, eventually, fight together. Many other men, however, enlisted for adventure or to escape from an arduous, dangerous or humdrum job.”

The rapid and unprecedented expansion of Britain’s land forces in 1914-1915 was a gigantic act of national improvisation which helped to create not only Britain’s first-ever mass citizen army but also the biggest single organisation in British history up to that time. Rallies and other public events were used, and considerable social pressure was brought to bear on men to volunteer, and those who did not risked vilification as ‘shirkers’ or cowards. The risks of poverty and destitution of their families, as the compensation offered to those who volunteered was insufficient to maintain them, was a disincentive for many men to volunteer. The messages put across on posters and at rallies emphasized a sense of duty – not only to their country but also to their families. One famous recruitment poster from 1915 shows a small child asking their father “What did you do in the war, Daddy?”

2,466,719 men joined the British army voluntarily between August 1914 and December 1915.